| Baccalieu Trail Heritage Corporation |

| ||||

|

|

|||

| ||||

|

|

||

|

The town of New Perlican is made up of two coves: Vitter’s Cove to the west and New Perlican harbour to the east. We began our survey on October 15, 2001 at the western end of Vitter’s Cove where some old stone foundations can be seen and walked east through Vitter’s Cove as far as Bloody Point at the entrance to New Perlican harbour. Along the way, we examining the beach and dug a number of test pits but found no evidence of an occupation dating to before around 1800. We had been told by some local residents that a fort had once stood at Bloody Point. However, we dug ten test pits in this area and found no evidence of a European occupation. Nor does there appear to be any documentary evidence for a fort. The only artifact we did uncovered on the point was a patinated chert core fragment. While this fragment could not be definitely assigned to any particular group, its presence indicates that the point was visited by aboriginal people at least once in prehistoric times. |

|

We had better luck on the western side of New Perlican harbour where we found two area that produced evidence of a seventeenth-century presence. One was on the beach just opposite the road leading up to Scott’s Hill. Here we found hundreds of fragments of English ballast flint probably dumped there by migratory fishing vessels. Along with the flint, we found fragments of water rounded pottery, dark green bottle glass and clay tobacco pipe stems. Most of this material was too fragmented and/or waterworn to be dated but an analysis of the clay pipe fragments suggests that this material was deposited over a roughly 150 year period from about 1650 to 1800. To our surprise, when we tested on the bank above the beach, we found no material older than about 1800.

About 70 metres south of this area and 30 metres back from the beach, we found a number of fragments of pottery dating to the late seventeenth or early eighteenth-century but these were mixed in with a large amount of nineteenth-century pottery and the entire area appeared to be quite disturbed. This area was just north of Mr. Russell Peddle’s house. Russell had served as a gunner during the Second World War and while we were surveying he celebrated his eighty-second birthday. Several times while we were testing on and around his property, he told us that the first people to settle New Perlican were the Heffords and pointed to an area on the eastern side of the harbour just north of the New Perlican River as the place where they had lived. Russell assured us that if we looked there we would definitely find “something old”. |

| We were working our way from west to east around the harbour and would have eventually tested in this area. However, Russell’s comments excited my curiosity. A few days later I visited the Provincial Archives in St. John’s to check the census records and it turned out that he was right about the antiquity of the Hefford name. The Berry census of 1675, our first list of Newfoundland planters, records a William Hafford and his wife living at New Perlican. They had one child, two boats and eleven servants. Also at New Perlican was a single planter called Edward House. Over time other planters came and went but the Heffords remained. The 1677 census also lists William, spelled ‘Efford’ this time, and his wife and states that their only child was a son and that they were employing six servants, owned one dwelling house, nine store rooms and lodging houses, two boats and one stage and kept a garden. In 1681 William, his last name spelled ‘Hellford’ this time, and his wife were still there and by this time William’s family had grown to include three children and he was employing ten servants. The Jones’ census of 1684 also lists Hefford (written Efford ), his wife and three children and, while the list of planters compiled in 1693 that was mentioned above does not provide names, it seems highly likely that the woman and six children it records living in New Perlican were the wife and children of William Hefford. Certainly the Hefford name continues in New Perlican throughout the eighteenth and into the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries. The Nominal Census of Trinity Bay for 1753 lists a James Hefford, his wife and two male children living in New Perlican and the Nominal Census for 1801 lists an E. Hefford married with one child living at New Perlican. Indeed, the most recent listings for the area indicate that there are currently three Hefford households in New Perlican with working telephones.

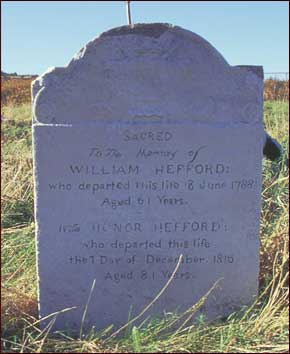

Russell’s prediction that we would find ‘something old’ on the east side of the harbour also proved correct. When we returned to New Perlican on October 26, I mentioned what Russell had said to the staff at the town hall. It turned out that they were aware of the Hefford connection and also knew the location of a headstone marking the grave of a William Hefford who had been born in 1727 and died in 1788. Clearly this was not the grave of the original William, but it seemed reasonable to assume that it was the resting place of his grandson. Indeed, it may be that the James Hefford listed in the 1753 census was one of the sons of the original William and that the William born in 1727 was James’ son. |

|